Journal #6

The Power of the Curve

Stephen Bayley, cultural commentator and co-founder of the Design Museum in London, discusses the allure of the female form in design

Published January 21, 2024

Updated April 12, 2024

Words by: Stephen Bayley

There is little doubt that the J Craft Torpedo’s styling evokes the dolce vita era when

Burton and Taylor inhabited Taormina’s Wunderbar, a haunt now tragically

abandoned to tourists. So, a J Craft’s visual appeal is partly based in a poignant sense

of loss and nostalgia for past glories. This is what aestheticians call the associational

response – a cache of memories released on sight. But its appeal is founded in

something more primal: a deep-rooted appreciation for the female form. This is the

direct aesthetic response we have to such a gorgeous shape. It works unconsciously

but is no less powerful for that.

Naval architects have developed a whole vocabulary to describe their art. There are

strakes, freeboards, forward sheers, rounded gunwales and some even talk of water-

plane area coefficients. But the most interesting is ‘tumblehome’, a term which

describes the way a hull, seen from front on, gets narrower as it rises above the

waterline. This has certain hydrodynamic advantages in terms of stability, which is

why the US Navy’s new Zumwalt-class destroyers feature dramatic tumblehome in

their design. Not only does the tumblehome design bring all these attributes to the J

Craft Torpedo, it also channels the historic inspiration of the feminine form in design,

by emulating the curves of a woman’s hips.

Then there are the other curves of the hull. To the human psyche, the female body is

a most familiar and intrinsic form. For reasons based in the foundations of the

brain’s architecture, a curve – because it suggests either maternal warmth and well-

being or an intimate encounter – touches a more profound part of the subconscious

than a parallelogram. Maybe this is because the female form is not right-angled.

Essentially, curves are more emotive than straight lines.

The iconic Coca-Cola bottle was inspired by the famous classical sculpture, Venues Callipyge

There is nothing new here. The most famous classical sculpture of Aphrodite, goddess of love, is called Venus Callipyge, which translates as “shapely bottom”. When pioneer design consultant Raymond Loewy wanted to explain the ineluctable appeal of the Coca-Cola bottle, he readily described its ‘Callipygian curves’. (Loewy did not create the bottle himself but was happy to be associated with this most successful of packages and his remark has gone down in design history).

Gerry McGovern, creative director of Jaguar Land Rover and responsible for the

transformation of Land Rover from supplier of agricultural equipment to

manufacturer of seductively desirable, luxury ground-transport, once took his

inspiration from shapely bodies working out in gyms. Marvel at the beautiful,

seamless surfacing of the current Range Rover and you will understand how inspiring

a gym can be.

A big quest in design research now is to prove – with the aid of dry electrodes and a

scanner tuned into the brain’s beta and gamma frequencies – the allure of curves

scientifically. Experimental results show that our neural colonies all get excitedly up

in arms when presented with a curve. Voluptuous shapes excite the part of the brain

that processes emotion, while angular shapes stimulate the dark core of your

amygdala, the brain’s fear centre.

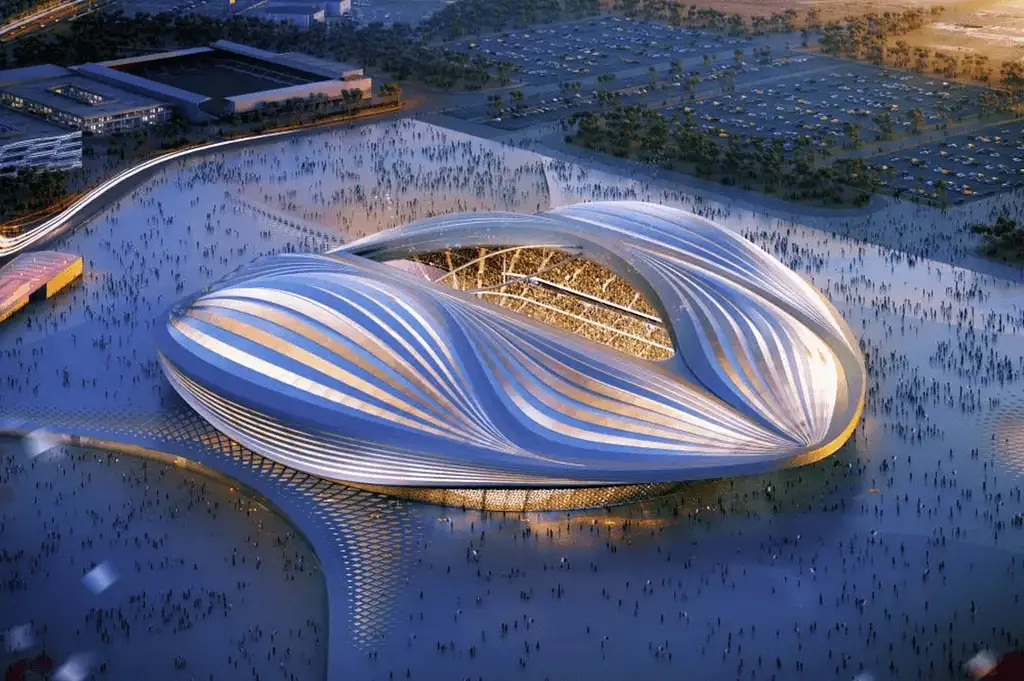

The history of art and design is littered with examples of the female form as a source

of inspiration. The plan of medieval churches was inspired by the female

reproductive system. In the 1955 Le Mans Vingt-Quatre Heures endurance race,

Carlo Mollino competed in an idiosyncratic design of his own invention whose two

hulls deliberately evoked female breasts. A controversial Anish Kapoor installation at

Versailles was inspired by the womb. And it is not just men who are inspired by the

female form. The world’s most famous, if not best, woman architect was Dame Zaha

Hadid who made her reputation with curvaceous shapes that are emphatically

feminine, such as her design for the Qatar 2022 World Cup with its dramatic almond-

shaped skylight.

In the desert or on the ocean, there is no getting away from the influence of the

female form in design.

Stephen Bayley is the co-founder, with Sir Terence Conran, of the Design Museum in

London, and is a cultural commentator, broadcaster, journalist and author. His many

books include Women As Design: Before, Behind, Between, Above, Below…; Design:

Intelligence Made Visible; and Cars: Freedom, Style, Sex, Power, Motion, Colour,

Everything.