Journal #8

Discover the hidden vineyards of Venice

Beyond the famous wines of the Veneto, a smattering of small-scale vineyards, within the city’s ancient religious sites, are passionately preserving historic winemaking and grape varieties

Published August 19, 2024

Updated August 22, 2024

Words by: Dr Christina Makris

In Venice, the discerning visitor just has to look for what is often hiding in plain sight to see what they wish to see. For any intrepid traveller, the city’s labyrinth of campi (squares) with their spry churches are architectural treasures there for the taking, and often conceal medieval convents and monasteries. These religious sites are also repositories for the knowledge of winemaking, making sacrament wine from their secret, well-kept gardens and vineyards for centuries.

It is common to find Prosecco, Soave and Valpolicella wines throughout the Veneto region. Yet, closer to the calli (narrow streets) and piazzas (squares) that culture lovers traverse on the Venetian archipelago itself, winemaking has existed for over 2,500 years. And, as a city built on the water, what better way to embark on a wine tasting journey of discovery than onboard your beautiful – and befitting of such a stylish city – J Craft Torpedo? Indeed, it is thanks to the endeavours of early mariners that the wines of this region flourished to become world-renowned.

The Venetian Empire inherited the love and cultivation of wine from their Roman predecessors. From the middle of the 14th century until the 16th century, Venice and its merchants controlled the entire wine market around the Mediterranean, from the east to North Africa, to the North Atlantic, in keeping with Roman imperial might. The famed Armada ensured these trade routes were sustained for centuries, and eventually, vineyards were planted even closer to freight and trade ports to accelerate production and trade of wine.

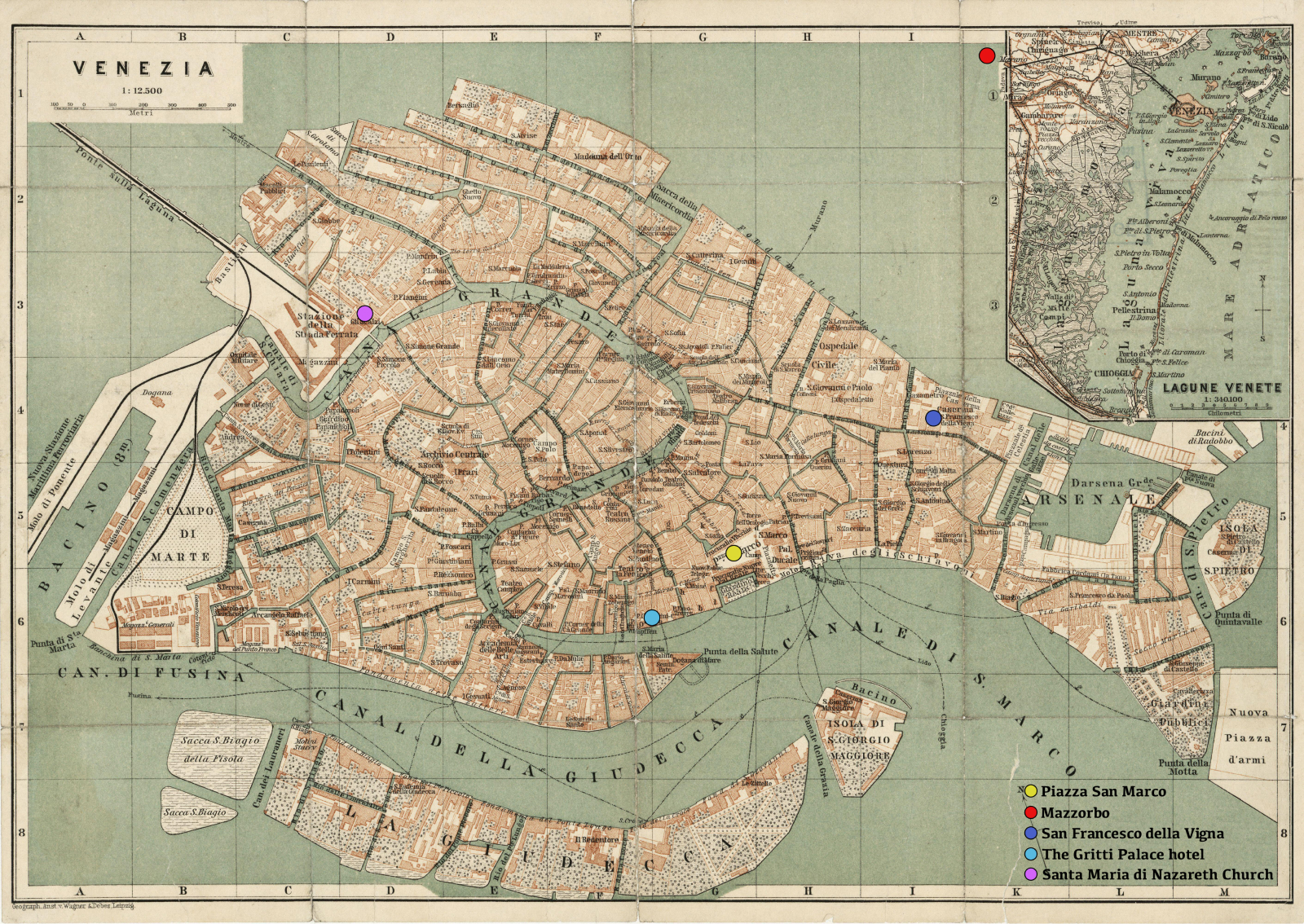

There were even vineyards in Piazza San Marco (St Mark’s Square) until 1100. The Napoleonic land register of 1812 measured 300 hectares of vineyards throughout the Venetian lagoon, but in 1966 a flood decimated many of these vines. Today, however, small- scale vineyards remain in a few religious sites, protected by abbey walls and passionate caretakers.

San Francesco della Vigna (San Francesco of the Vines) in Castello is the oldest vineyard in the city, dating back to the 13th century. The Doge Andrea Gritti financed rebuilding the church in 1534, and 30 years later it was given a facelift by the renowned architect Andrea Palladio. The cloisters conceal vineyards purchased in 2019 by the Santa Margherita winemakers, whose agronomists, with the help of the monks, reintroduced lost grapes and began collecting rainwater for irrigation. The wine, Harmonia Mundi, is produced in limited amounts (around 1,000 bottles per year) and proceeds support the students at the Institute of Ecumenical Studies of the Faculty of Theology and the restoration project for the Chapel of San Marco. The dry wine produced, Harmonia Mundi, is made of the late-ripening red Refosco grape, with its taste of plum on the tongue and peppery spices on the palate. Approach this square from the nearby ancient Arsenale to imagine what it felt like to be part of the Republic’s naval force, before Venice gained its epithet La Serenissima (the most serene).

Next, motor around the Grand Canal, looping your J Craft Torpedo smoothly around Cannaregio, until you reach the Santa Lucia railway station, where you will find the Church of Santa Maria di Nazareth and the convent of the Discalced Carmelites dates to 1649. Its vineyards are hidden by a brick wall and are designed on elements of Christian numerology, celebrating the number seven, which features in the visions and writings of Saint Teresa of Avila, the Patron Saint of the Order. In 2010, the Venice Wine Consortium, a trade association that represents artisanal winemakers in the city, reignited the cultivation of grapes in the Carmelites’ garden, focusing on 17 indigenous varieties in a bid to preserve the biodiversity of lagoon flora. Featured grapes include the Venetian Dorona, Malvasia, as well as Armenian and Holy Land varietals. The monastery’s red wine is Prandium Raboso, using grapes such as Marzemino, Turchetta and Recantina. Their white wine, Ad Mensam, uses local grapes including Verduzzo Trevigiano, Glera, Grapariol and Malvasia. The production is small, around 900 bottles a year, and can only be purchased directly from the abbey.

The spirit of preserving knowledge and regeneration is also found a 35-minute boat ride along the archipelago, on the small island of Mazzorbo, which should be the next stop. Here, Gianluca Bisol of the Bisol sparkling winemaking dynasty decided to redevelop the land for grape growing. He discovered four unfamiliar varieties in the garden of the 7th-century Byzantine Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, on the neighbouring island of Torcello. One was the Dorona di Venezia, a varietal exclusive to the lagoon, which was nearly driven to extinction. This Uva d’Oro (Golden Grape), was once the most expensive grape – favoured by Venetian noblemen and Doges – and its cultivation had dwindled when disease and economics altered winemaking in the region. It was almost completely lost in 1966.

The Bisol family decided to explore cultivation on these islands and planted 4,000 vines of Dorona on the Scarpa Volo Estate, an abandoned Benedictine monastery on Mazzorbo. Gianluca enlisted the expertise of oenologist Roberto Cipresso to develop wines that capture expressions of lagoon terroir: white peach, honey, wormwood, and salt. Each of the 5,000 bottles produced every year are hand-numbered with a gold-leaf label, made by the Battiloro – the last goldbeating family in Venice – and can only be purchased directly from the winemakers. The estate, Venissa, also hosts a Michelin-starred restaurant of the same name, with dishes prepared by Chiara Pavan and Francesco Brutto using lagoon seafood and produce grown on the archipelago.

These vineyards and wineries can all be accessed in one day by boat. After a day of ruling the lagoon waves, why not moor up at The Gritti Palace hotel for a well-earned spritz or Franciacorta on their terrace overlooking the Grand Canal. Boating connoisseurs will recognise the mahogany woodwork of the deck, tables, as well as the leather seats and silver railings are designed by and modelled on classic boat company, Riva, for silver-screen retro-glamour.

Today, these classic and glamorous boating aesthetics live on in J Craft, embodied in the beautiful design and styling of the Torpedo, which ignites the spirit of yesteryear as you cruise the canals and waterways of Venice’s unique and enchanting environs.

The surviving vineyards in the Venetian lagoon are symbols that uphold the ongoing history and pleasure that has always been available to visitors in Venice. However, they also forge a path forward to a sustainable future for once-endangered grapes and wines that are as much a part of the Venetian story as its art and culture.

Dr Christina Makris is an author, restaurant philosopher and the wine columnist for Apollo art magazine